For the past decade, Congress has been defined by small majorities and partisan gridlock. It is easy to forget that at times during President Obama’s first Congress, the Democratic caucus had a 60-seat majority in the Senate, or that President Obama’s cabinet included several conservative members. More recently, small majorities and a lack of bipartisanship have led to intense standoffs between lawmakers. For instance, during the Supreme Court nominations during President Trump’s administration and the upcoming debt limit fight President Biden’s administration is facing.

As these barriers to policy making have taken hold, we have seen Congress become increasingly reliant on little-known tools and procedures that allow them to avoid the Senate’s 60-vote thresholds and legislate with smaller majorities. Knowledge of these tools is crucial to understanding how Congress has passed major legislation, like the Inflation Reduction Act, and what proposals have viability to pass into law moving forward. Here are five tools Congress can use to affect change amidst partisan deadlock:

The Congressional Review Act

A path for Congress to reverse federal agency rulemaking.

The Congressional Review Act (CRA) is an oversight tool that Congress established in the 1996 Small Business Regulatory Enforcement Fairness Act to grant themselves additional oversight of the federal rulemaking process. The CRA requires federal agencies to report to Congress on any rules they issue and allows members of Congress to file a joint resolution of disapproval in an effort to overturn the issued rule within 60 legislative days of the rule being reported. While most legislation requires 60 votes to pass the Senate, joint resolutions require only a simple majority, making them a useful tool for a party with a slim majority.

The CRA has emerged as a popular tool for incoming administrations to use to disallow rulemaking finalized during the previous administration. There have been 20 successful joint resolutions of disapproval, with one passed early in the Bush administration, 16 passed during the Trump administration, and three passed so far during the Biden administration.

In eight additional cases, both chambers have passed joint resolutions of disapproval to oppose a rulemaking action taken by a sitting administration. Each has been predictably vetoed. Two joint resolutions of disapproval were passed by Congress and quickly vetoed by President Biden between February and April 2023. The first would have overturned a Department of Labor rule allowing retirement-plan managers to consider factors like climate change in their investment decisions. The second would have overturned a rule expanding environmental protections under the Clean Water Act.

Congressional Intervention in the District of Columbia’s Legislative Process

A limited, but powerful, role that Congress plays in the governing of Washington, D.C.

While the Council of the District of Columbia’s legislative processes mostly align with state legislative processes, it differs significantly in that legislation passed by the D.C. Council must undergo a period of congressional review. Once a bill is signed by the Mayor or the Council overrides their veto, it becomes an Act and is sent to Congress for review. In most cases, Congress then has 30 days during which it can introduce a joint resolution disapproving of the Act. If passed by Congress and signed by the President, the joint resolution prevents the Act from becoming law.

Successful Congressional intervention is incredibly rare. In fact, when President Biden signed a resolution blocking a D.C. Council-passed Act that would have rewritten criminal sentencing laws in March 2023, it was the first such action in more than thirty years.

The Filibuster

A minority party’s favorite way to block passage of a bill.

Although most measures require only the votes of a simple majority to pass the Senate, we often hear of the need for the support of 60 Senators in order for a bill to have a chance at passage. This is because of the filibuster. The rules of the Senate generally allow for unlimited debate on measures, which can only be ended by 60 Senators voting to invoke “cloture”, which limits further debate on the measure to a maximum of 30 hours. The filibuster means that a minority of Senators may prevent a vote on a bill by refusing to invoke cloture and start the process to proceed to a vote.

Historically, the filibuster has been used in attempts to block additional war powers during World War I, civil rights legislation in the mid-20th century, and judicial nominations in the 2000s. Reactions to each of these have resulted in the filibuster being weakened in some ways, and simply modified in others. We are left with a filibuster that does not actually require a Senator to speak on the floor to block legislation (as was the case before the 1970’s), and which does have certain exceptions as discussed in numbers 4 and 5 below.

While somewhat weakened, the filibuster remains an incredibly powerful tool that prevents a party with a simple majority, but not a 60-vote majority, from governing without some participation from the minority party. Recent partisan priorities like the Republican push to repeal the Affordable Care Act and Democratic efforts to raise the minimum wage have been hampered by the use of the filibuster by a minority group of Senators.

Reconciliation

An increasingly relied upon procedure to pass congressional priorities with a simple majority.

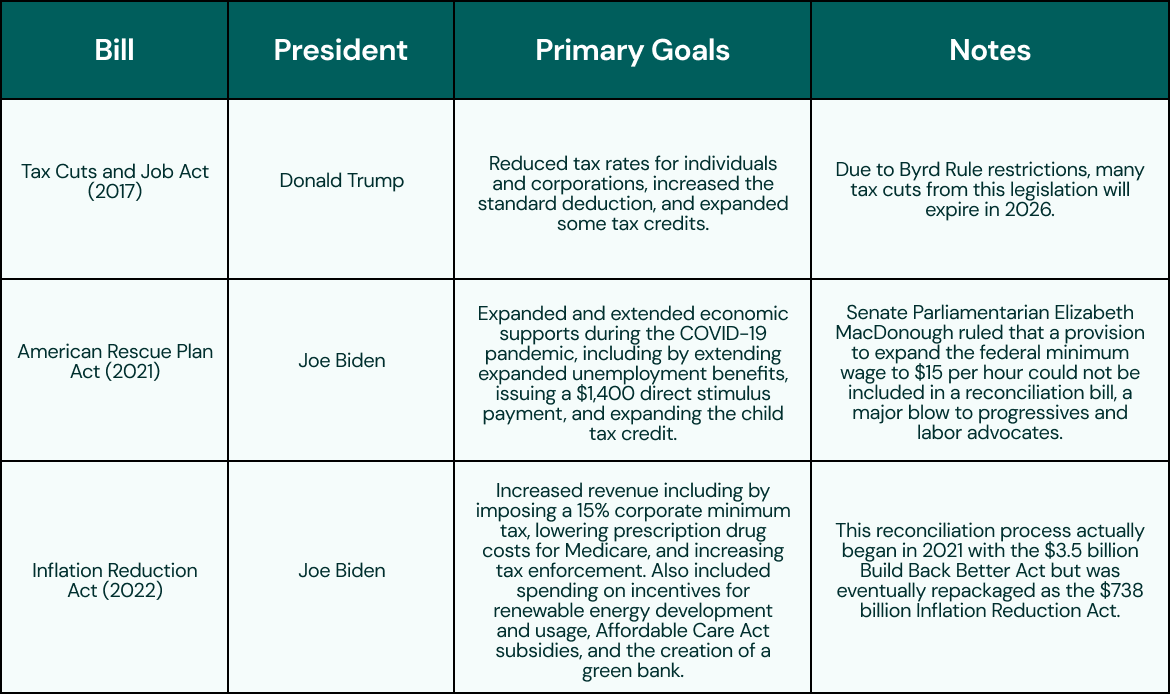

Created by the Congressional Budget Act in 1974, reconciliation is a special parliamentary procedure that allows for certain budget legislation to move through the Senate more quickly and with less support. Debate on reconciliation bills is limited to twenty hours, meaning that the 60-vote majority to end a filibuster that is needed for most legislation is not necessary and the bill can be passed with a simple majority.

Restrictions, mostly stemming from the Byrd Rule, limit what proposals can be included in a reconciliation bill. Among other restrictions, the Byrd Rule limits reconciliation bill provisions to only those that impact spending or revenues, prevents any provisions that would increase the federal deficit beyond ten years, and blocks any changes to Social Security. Decisions on whether a reconciliation bill meets the requirements set by the Byrd Rule are referred to the Senate Parliamentarian for interpretation.

Congress may pass one reconciliation bill per year impacting revenue, spending, and the federal debt limit,up to a theoretical total of three bills. In practice, Congress generally passes at most one reconciliation bill in a year, impacting each of the three topics listed above.

Twenty three reconciliation bills have been signed into law since the procedure was first used in 1980. An additional four reconciliation bills have passed Congress, but were vetoed by the President.

The Nuclear Option

The omnipresent tool of last resort.

While the 60-vote majority to invoke cloture, end debate, and move legislation forward in the Senate is central to the Senate’s legislative process rules, changing those rules only requires a simple majority. This intricacy means that anytime a simple majority is road blocked by the threat of a filibuster, they do have the option of changing Senate rules to reduce the need for that 60-vote majority. Changing those rules in any fashion is controversial, and is generally referred to as the “nuclear option.”

Use of the nuclear option has long been debated, threatened, and used as a bargaining chip. It wasn’t truly deployed until 2013, when Democrats removed the 60-vote requirement to invoke cloture and end debate on judicial nominations except for the Supreme Court. This allowed Democrats to overcome Republican filibusters of the Obama administration’s judicial nominations.

In 2017, a Republican Senate majority invoked the nuclear option to expand the changes made in 2013 to apply to Supreme Court nominations as well. This move allowed for the Supreme Court nomination of Neil Gorsuch,and later Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barett, to pass with a simple majority.

Since 2017, the nuclear option hasn’t been invoked, but both President Trump and President Biden have hinted at supporting its use to allow for certain legislation to pass with a simple majority. Debates over the debt limit, government funding, and abortion rights have all seen the nuclear option considered, but not used, in recent years.

While these tools can make Congress’ actions harder to predict, follow, and understand, the policies they enact are just as important and impactful to our daily lives as legislation passed through traditional means. Being aware of each way that Congress may affect change is essential to following the modern federal legislative process.

Interested in learning how Plural can help unlock powerful legislative insights into Congressional actions and the modern legislative process? Book a demo today!