The constant evolution of the budget process, coupled with how much of the negotiations happen behind closed doors, can make following the process intimidating. But the outsized impact of these large legislative packages, along with the regularity with which Congress must engage in this process, makes following the budget essential. Understanding the key steps in this process will put you on the right path to being the budget expert in your organization.

What Is the Federal Budget Process?

The modern federal budget process, largely defined by the Congressional Budget Act of 1974, is the prescribed timeline by which the federal government should determine its annual spending and revenue levels each year. The government’s fiscal year runs from October 1 to September 30, and the budget process lays the tracks for each of the involved parties, including federal agencies, both chambers of Congress, and the President, to influence, debate, and approve funding for the next fiscal year ahead of the October 1 deadline.

Increasingly over the past 15 years, Congress has deviated from the federal budget process’ deadlines by missing deadlines or skipping steps. While it seems counterintuitive, amidst the uncertainty of the informal budget process that exists in practice today, a greater understanding of the traditional budget process is vital to understand where Congress is, and where they must get to, in order to keep the government funded.

Mandatory and Discretionary Spending

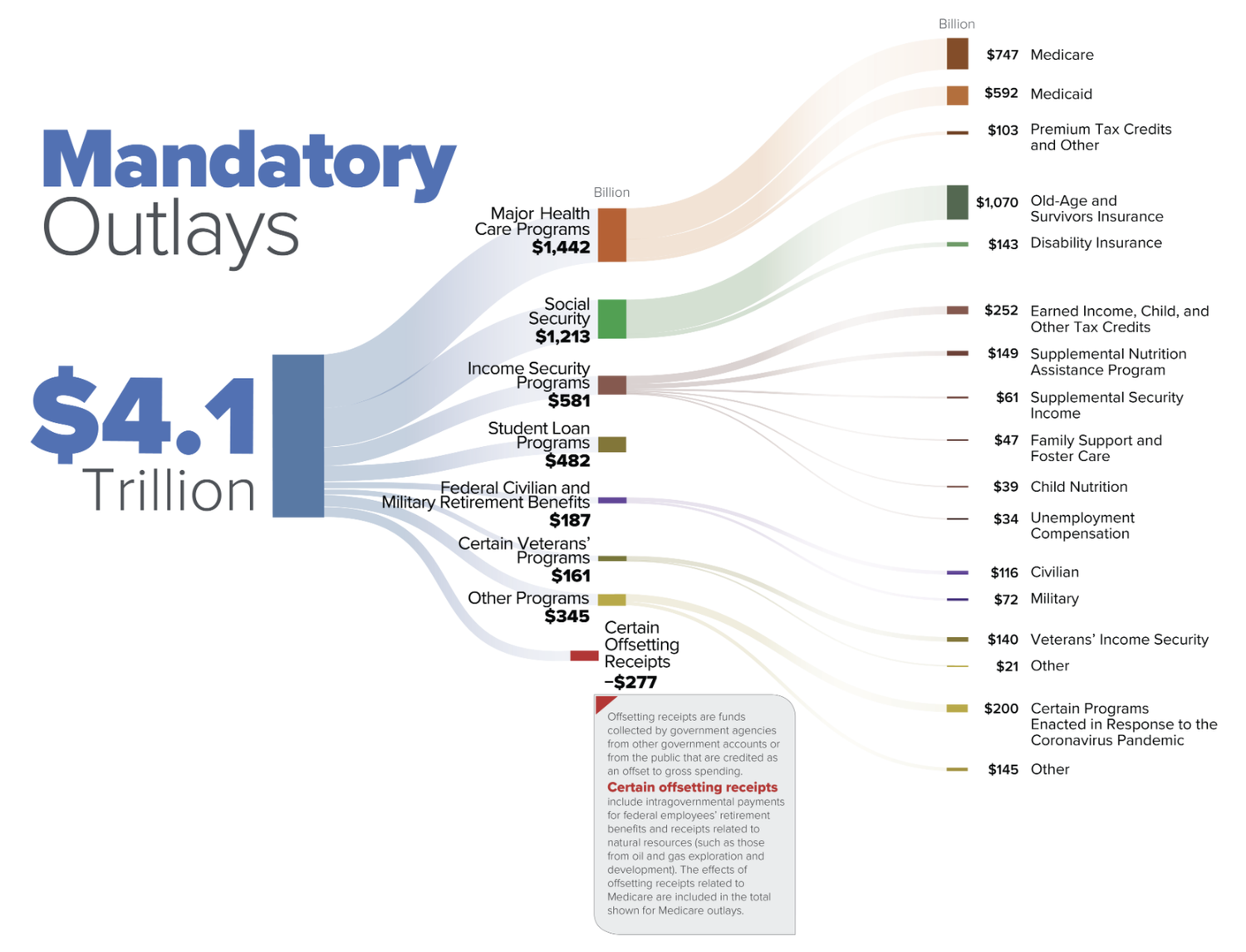

Federal spending is commonly categorized into two distinct categories, mandatory spending and discretionary spending —interest payments on existing debt make up the remainder of the government’s spending budget.

Mandatory spending includes funding for programs that have their funding levels determined by existing law. Most mandatory funding categories are determined by existing laws, which establish social benefit programs, like Social Security, and set forth the criteria used to determine who is eligible. Spending on Social Security, therefore, is determined by how many individuals are eligible, and the benefits they are owed as defined by existing law, making it mandatory spending. The only way to impact mandatory spending is for Congress to amend that existing law, typically by expanding or restricting eligibility to these programs.

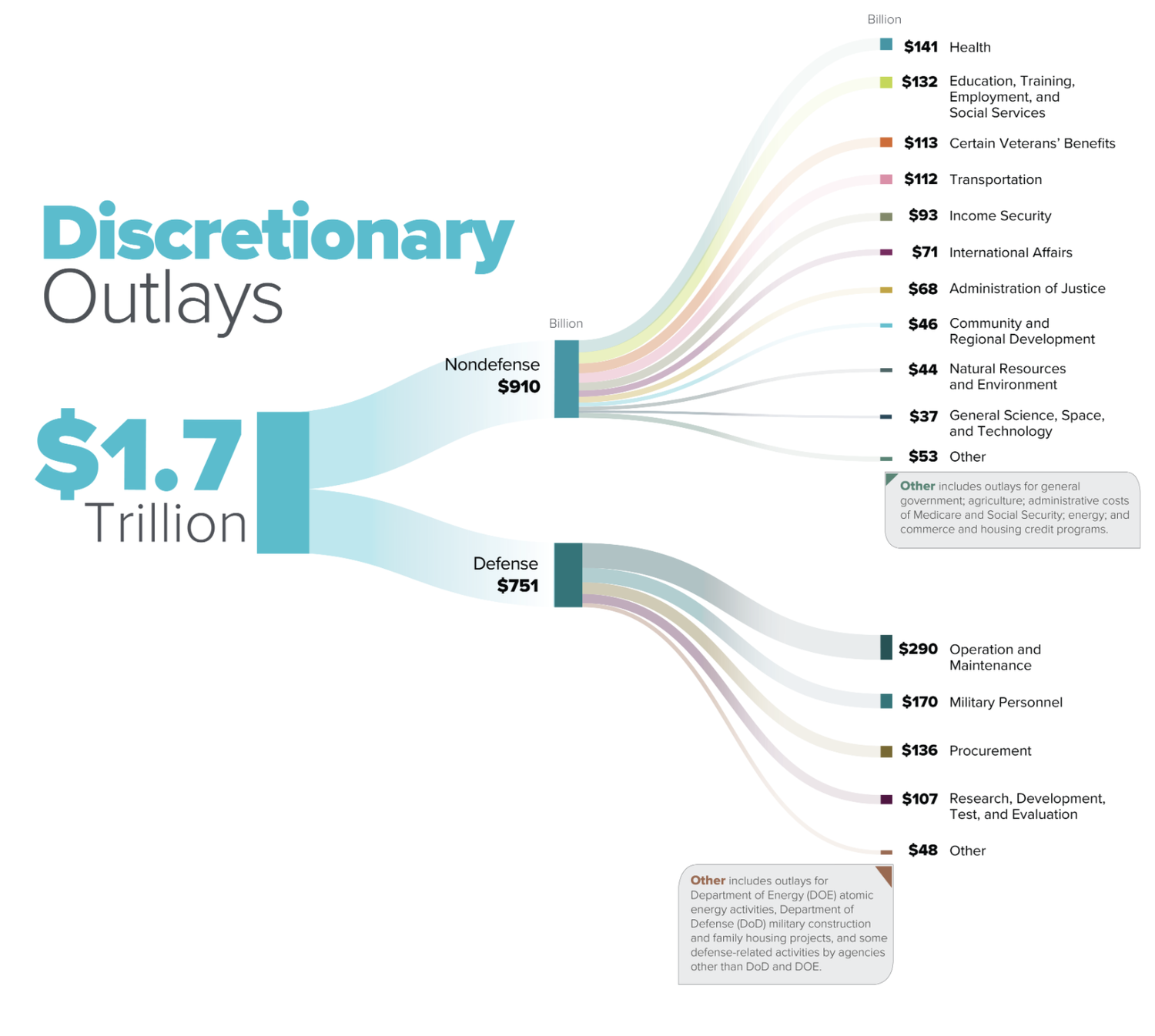

By contrast, the dollar amount and specific use of discretionary spending is not determined by any existing law. Despite its name, discretionary spending is no less important than mandatory spending, as it is the tool that Congress uses to fund the federal agencies responsible for education and defense programs, along with many other priorities. For example, a large portion of discretionary spending is directed towards agencies like the Centers for Disease Control and the National Institutes of Health, for their work researching and improving public health. Under the federal budget process, discretionary spending is formulated, debated, and passed by the House and Senate Appropriations Committees.

Spending vs. Revenues

Like any budget, the federal budget balances spending against income, known as revenues. The government’s revenues are derived from taxes and fees that,like mandatory spending, are traditionally determined by existing law. During the budget process, Congress can attempt to change revenue levels by amending existing tax law, or passing new tax law. However, this isn’t a necessary component of the budget process, and revenues generally receive less consideration than discretionary spending.

Stages of the Federal Budget Process

The incredibly complex and important process of appropriating and receiving trillions of dollars can be understood in the following 4 steps:

- The President’s Budget Submission – Generally submitted in early February, this is the President’s opportunity to lay out their proposed spending plan for the next year.

- Congressional Hearings – Following the release of the President’s Budget Plan, Congressional Committees hold hearings for agency leaders to promote and defend the President’s proposed funding for their agencies.

- Budget Resolution – After consideration of the President’s proposal, and hearing from agency leaders, the House and Senate may pass their outline of a budget proposal, known as a Budget Resolution.

- Consideration and Passage of Appropriations Bills – Following the limits set by the budget resolution, the House and Senate Appropriations Committees consider and pass bills that detail spending on discretionary programs in the next fiscal year, known as Appropriations Bills. Following passage out of committee, these bills are voted on by the full chambers, and any differences between proposals will be worked out in Conference Committee before a final passage is sent to the President for their signature.

In practice, the budget process can often deviate from these four steps, and include other tools and procedures.

The President’s Budget Submission

Kicking off the annual budget process is the President’s Budget, typically submitted in February. This detailed report is the result of months of hard work by agency staff and includes top-level recommendations for government expenditures and revenues, as well as proposed spending in the 20 budget function categories, including transportation, Social Security, national defense, and so on.

While incredibly detailed, the President’s Budget holds no legal authority, and is generally quite different from what ultimately ends up being passed into law. With that being said, this is one of the President’s best opportunities to turn their campaign promises into proposed policy before Congress.

Congressional Hearings

Each spring, both chambers of Congress host congressional hearings to question agency heads about the proposed funding for their programs as outlined in the President’s Budget. Depending on the partisan makeup of Congress, and the agency leader, these hearings can be some of the most contentious on a Committee’s calendar. Just as the budget submission is an opportunity for the President to lay out their priorities, these hearings are an opportunity for members of Congress to challenge those priorities, or offer their own priorities.

The Congressional Budget Resolution

Following these hearings, Congress may release its own outline for the next year’s budget, known as a budget resolution. This proposal is first created by the House and Senate Budget Committees, before being passed by each chamber. Compared to the President’s Budget Submission, a Congressional Budget Resolution is far less detailed, typically outlining just overall spending and revenue targets, and offering some direction to appropriations committees. This resolution may also include reconciliation instructions that direct a committee to produce legislation making changes to mandatory programs or revenues. As a concurrent resolution, this plan must be approved by both chambers of Congress, but it is not signed by the President and does not become law.

It is important to note that Congress is not required to pass a budget resolution. Since 2000, Congress has only passed a budget resolution around 50% of the time. Instead, the House and Senate often instead pass “deeming resolutions”, which allow individual chambers to proceed on budget-related work without coming to an inter-chamber agreement first.

Appropriations Bills

With spending targets set, either through a budget resolution or other means, House and Senate Appropriations Subcommittees conduct hearings to deliberate on the budget(s) of the agencies and programs under their jurisdiction. The subcommittees pass their subject-specific bills out to the larger Appropriations Committee, where the full committee votes on sending the bill to the floor of the House or Senate.

Once these appropriations bills reach the floor of their chamber, the full legislative body will debate and vote on the proposals. Resulting from this process is two sets of appropriations bills, one House-approved and one Senate-approved, that a Conference Committee consisting of members from both chambers then considers and combines into a consolidated proposal. The Conference Committee proposal then must pass the Senate and House once more, before heading to the President’s desk for signature.

In theory, the bill should be signed by the President in advance of the October 1 fiscal year beginning, so that the government is consistently funded. However, as explained further below, the process to pass an annual budget can often stretch well beyond the beginning of the fiscal year.

Visualizing the Federal Budget Process With a Flowchart

Understanding the federal budget process is key to understanding how our government works and developing strategies to achieve your organization’s goals.

Other Considerations

Reconciliation

As mentioned above, the Congressional budget resolution may contain reconciliation instructions that direct certain committees to consider and pass legislation, making specific changes impacting spending, revenues, or the debt limit. These instructions only direct the specific committees to pass legislation that makes a certain impact to spending, revenues, or the debt limit, and do not dictate the specific policies that should be enacted.

Because these bills are derived from the Congressional Budget Resolution, as outlined by the Congressional Budget Act, they are able to move through the Senate without needing its usual 60-vote majority to end a filibuster (more on that here).

The Debt Limit

Connected to the federal budget process, both procedurally and politically, is the issue of our national debt. Federal government spending typically outpaces the revenues generated by taxes and fees, resulting in a deficit that increases our national debt year after year. Since World War I, Congress has regularly authorized new borrowing to cover those deficits by raising or suspending a cap on the amount of debt that the government is allowed to hold, known as a “debt limit”.

If the government were to hit the debt limit, it would be unable to meet its debt obligations and would begin to default. Defaulting, which the U.S. has never done, could have disastrous impacts on the domestic and global economy. It is because of the disastrous impacts of default that Democrats and Republicans often tie policy priorities to the debt limit. If one party views increasing the debt limit as essential, the other party may see an opportunity to demand a partisan priority, like spending reductions, in order to commit their support. The debt limit has often been suspended until the beginning of the fiscal year so that the two Congressional tasks of funding the government and ensuring it doesn’t hit the debt limit are tied together.

What Happens if Congress Doesn’t Pass a Budget by October 1?

Outside of passing an annual budget outlining funding for the next fiscal year by October 1, Congress has two options: 1) Pass a continuing resolution or 2) Enter a government shutdown.

By far the less disruptive option, a continuing resolution simply leaves in place existing funding levels, sometimes with small adjustments, for agencies and programs as they were during the previous fiscal year. Continuing resolutions generally expire once a proper budget has been passed or a certain date has passed, whichever comes first. Continuing resolutions offer negotiators in Congress extra time to work out a budget agreement without entering a government shutdown. An increasingly popular tool, there have been 33 continuing resolutions passed in the past 10 years.

Absent a comprehensive budget bill or a continuing resolution, the government enters what is known as a shutdown. During this time, only the “essential” services and functions remain active, like active duty military employment and programs relying on mandatory spending. “Non-essential” government employees may be furloughed, and government-run facilities like museums and national parks may be closed. Similar to hitting the debt limit, the negative impacts of a government shutdown are often used as a bargaining chip in partisan budgetary negotiations. The government has shut down three times in the past ten years, for a total of 54 days.