The Electoral College may not be a school, but learning about it will give you a useful education on United States presidential elections.

The term “Electoral College” refers to the group of people who cast direct votes for the president and vice president of the United States. These positions are not directly chosen by citizens in a popular election. When a voter marks a ballot for a presidential candidate, they are really voting for a slate of electors who pledge to vote for that candidate. The winning slate becomes part of the Electoral College. Learn more about the Electoral College’s history, how it works, and how it affects U.S. politics below.

History of the Electoral College

When the Founding Fathers drafted the U.S. Constitution, some proposed that Congress elect the President. Most delegates to the Constitutional Convention eventually rejected this idea because it could violate the separation of powers between government branches. Others suggested a direct election by qualified citizens, but some delegates were concerned that citizens would be too uninformed or too likely to be swayed by populism. Delegates from slave states also objected that this would give them less influence.

When delegates decided on Congressional representation, they came to the Three-Fifths Compromise. Three-fifths of a state’s slave population would count for the apportionment of representatives. The Founders then agreed that each state would be allocated electors based on their Congressional representation. These electors would be elected by citizens and meet to vote for the president. In the case of a tie, the House of Representatives would decide the winner, with each state contingent getting one vote.

At first, electors cast votes for two presidential candidates. The candidate receiving the most votes became President and the runner-up became Vice President. After a contentious election in 1800, Congress proposed the 12th Amendment to the Constitution, which requires electors to cast separate presidential and vice presidential ballots.

Many state legislatures chose electors in the first several presidential elections. By 1832, all states except South Carolina had switched to a popular election by citizens. South Carolina’s legislature continued to choose its electors until 1860.

How Does the Electoral College Work?

The Electoral College has the simple task of meeting and voting every four years. However, it is part of a larger, more complicated process.

The Allocation of Electoral Votes

Each state is allocated a number of presidential electors equal to the size of its Congressional delegation. That’s the number of members of the Senate — two for each state — and the House of Representatives combined.

Currently, there are 538 electors in the Electoral College. This includes 535 from the 50 states and three from Washington, D.C., which does not have voting representation in Congress but is still allocated presidential electors. Presidential electors are reallocated every ten years based on the U.S. Census population counts. The total number of electors has grown over time but has not changed since 1964.

To win the presidency, a candidate must receive an absolute majority of electoral votes, which is 270. All but two states allocate all of their electors to the statewide winner of the popular vote. Maine and Nebraska each allocate two electors this way, and they allocate the rest according to the popular vote in each Congressional district. The winner in Washington, D.C. is assigned all three of its electors.

The Role of Presidential Electors

Under the Constitution, electors cannot be members of Congress or hold federal office. Otherwise, elector selection is left up to the states. In most states, each political party nominates a slate of electors at its state convention. In others, each state party committee chooses its electors.

The Constitution does not require electors to vote for the winner of their state’s popular vote, though some states do. Still, “faithless electors” who do not vote for their pledged candidate are rare. There have been only 165 faithless electors in American history, including 71 whose candidates died before the votes were cast.

When the United States first began, electors did not pledge to vote for any candidate. The Founders intended for them to decide based on the will of the people. Over time, more electors began pledging their support for presidential candidates. This became a standard part of the process by the mid-19th century. By the 20th century, most presidential ballots featured the candidate’s name. Electors still appear on the ballot underneath their presidential candidates in a few states, but most states now only list the candidates themselves.

Certifying the Presidential Election

After the election results are counted, each state performs a canvass where they double-check the results. They then certify their elections, determining which electors will be part of the Electoral College.

Each state’s members of the Electoral College meet on the first Monday after the second Wednesday in December. From their own states, they cast their electoral votes for President and Vice President. They send these votes to Congress, which meets on January 6 to count them.

Electoral College Criticisms and Controversy

The Electoral College has drawn its share of criticism and controversy.

Popular Vote vs. Electoral College Votes

It is possible for a candidate to win the Electoral College without winning the popular vote. This has happened in four elections in American history – 1876, 1888, 2000, and 2016.

Lowers Turnout

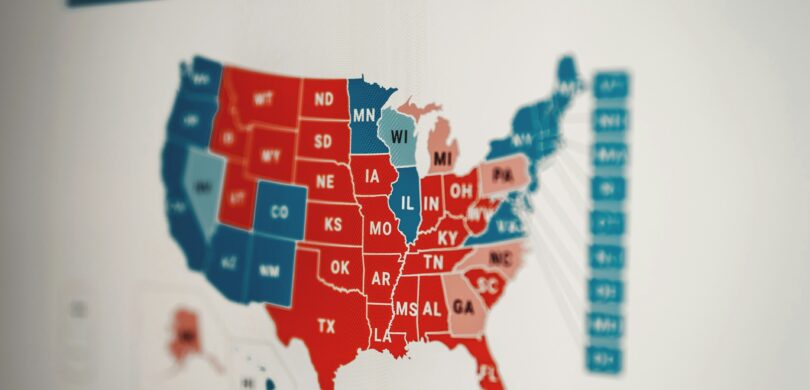

Critics of the Electoral College argue that its winner-take-all nature lowers voter turnout. Voters in strong “red” (Republican) or “blue” (Democratic) states may not show up to the polls if they don’t believe their presidential vote will count.

This also could hide any disenfranchisement within states. If a state makes it harder for a group of people to vote, this reduces turnout for that group but does not affect the overall electoral vote count.

Unequal Voting Power and Influence

The apportionment of presidential electors favors smaller states, which have a proportionally larger share of the electoral vote than larger states. Candidates also tend to campaign almost entirely in “swing” states that could swing one way or the other in the election.

Supporters argue that the Electoral College balances the interests of rural, less populous states and more populous urban ones. It also limits the amount of money spent on presidential elections by focusing campaigns on a few key states.

No Votes For U.S. Territories

Residents of U.S. territories cannot vote for President of the United States. This includes the four million residents of American Samoa, Guam, Puerto Rico, the Northern Mariana Islands, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. Individuals living in these territories do not have voting representation in Congress or the Electoral College.

Disadvantages Third Parties

Smaller political parties are unlikely to make a meaningful challenge for President in a winner-take-all system. The last time a third party claimed any electors was in 1968, when George Wallace won five states and 46 electoral votes.

Faithless Electors

Faithless electors are those who do not vote for their pledged candidate. They’re rare, and have never changed the outcome of a presidential election. However, this remains a possibility.

The 2020 Election

After the 2020 election, vote counts showed that presidential candidate Joe Biden would win a majority of electoral votes. Incumbent President Donald Trump and his legal team planned to convince several states to certify “alternate” slates of electors pledged to Trump. None of these states certified the alternate slates. In some states, they met anyway and signed documents with illegitimate electoral votes. This did not affect the Congressional certification, even when rioters broke into the Capitol building on January 6, 2021, to try to change it.

Efforts to Reform the Electoral College

There have been more than 700 proposals introduced to remove or reform the Electoral College. Learn more about some of the most notable attempts below.

Bayh-Cellar Amendment

In the 1968 election, Richard Nixon received 301 electoral votes to Hubert Humphrey’s 191. Nixon’s margin of victory in the popular vote was much narrower – 43.5% to 42.9%. This led the U.S. House of Representatives to approve an amendment to abolish the Electoral College in 1969. The Bayh-Celler Amendment, proposed by Sen. Birch Bayh and Rep. Emanuel Celler, would have set up a two-round system. The winner of the national popular vote would win the election if they received more than 40% of the vote. If multiple candidates hit that threshold, the winner would be decided in a runoff election.

Some lawmakers from Southern and smaller states opposed the amendment, saying it would cause their states to lose influence. When the Senate debated the amendment, opponents began a filibuster – a delay tactic to prevent a vote. Supporters did not have enough votes to break the filibuster, and the proposal never passed.

Carter Proposal

In 1977, President Jimmy Carter sent a letter to Congress with several proposed election reforms. These included a Constitutional amendment for the direct election of the president. The Senate debated such an amendment but, once again, failed to pass it after a filibuster.

National Popular Vote Interstate Compact

The National Popular Vote Interstate Compact (NPVIC) is an agreement that participating states will allocate all of their electoral votes to the popular vote winner. It will come into effect only when enough states adopt it for a total of 270 electoral votes – the majority needed to win a presidential election. As of May 2024, 17 states and Washington, D.C., have adopted the NPVIC, totaling 209 electoral votes.

14th Amendment Litigation

In 2018, lawsuits were filed in four states – California, Texas, Massachusetts, and South Carolina – challenging the constitutionality of the Electoral College. The nonprofit group Equal Citizens argued that a winner-take-all allocation of presidential electors violates the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. The lawsuits were unsuccessful.

Get Started With Plural

As the 2024 election nears, understanding the Electoral College is especially crucial. At Plural, we’re committed to helping public policy teams, advocates, and citizens alike understand government and legislation. Create a free account today to:

- Search legislative data from 53 US jurisdictions: 50 states, Washington, D.C., Puerto Rico, and U.S. Congress

- See comprehensive bill details, state-specific data, and legislator information

- Easily track bills and never miss an update

- Receive daily updates on the bills you’re monitoring

More Resources for Public Policy Teams

Key Benefits of AI for Lobbying & Advocacy

Want to be able to explain the benefits of artificial intelligence for lobbying and advocacy? Everyone is talking about AI. And we get it, it’s not simple to understand. But as an AI-powered organization, Plural is here to help you get the most out of advancements in AI to make your job as a policy […]

2025 Legislative Committee Deadlines Calendar

Staying on top of key deadlines is manageable in one state, but if you’re tracking bills across multiple states, or nationwide, it quickly becomes overwhelming. That’s why we created the 2025 Legislative Committee Deadlines Calendar. Stay ahead of important dates and download our calendar today. Get started with Plural. Plural helps top public policy teams get […]

End of Session Report: Florida 2024 Legislative Session

The 2024 Florida legislative session saw significant activity in the realm of insurance and financial services, reflecting key themes of consumer protection, market stability, and regulatory modernization.